During research for a novel I hope to write, I ran across the novel, The Last Ballad, written by Wiley Cash. Cash’s novel is a fictionalized glimpse into the life and final months of union organizer and balladeer, Ella May Wiggins. The story was inspired by actual events that hit a little too close to home. Cash paints a historical picture that is both historically accurate and vivid, yet is as dark as the interiors of the textile mills he writes about and the lives of the people forced to work in them. It’s a novel I wish I could have written.

Wiggins, a spinner at Bessemer City’s American Textile Mill #2 with a history of bad choices for many right reasons and some not so right, was shot and killed in 1929 during labor unrest leading up to the Loray Mill Strike in Gastonia, North Carolina, April 1,1929 and ending in the collapse of the strike after Wiggins’s death in September of the same year.

It was the end of the period called “The Roaring Twenties” which for the textile workers and farmers of the South, were anything but roaring. While Wiggins did not live to see the great Wall Street crash, times were already hard for those who toiled in textiles, many who had just earlier been left destitute from falling farm prices. As my grandmother often stated, “We lived so hard we didn’t notice the Great Depression.”

For anyone with empathy, the book is a tough read. It is painful on many levels, not just Wiggins’s death. It is disturbing because I see a certain parallel with “history repeating itself.”

I grew up a “hill milly”. My youth was tied both to the fields of corn and beans of my grandparents and to the textile mills of my parents. By the time I cleaned the cow manure off my boots and traded square bales of hay for the lint, heat, and noise of the Springs Mills’ White Plant in Fort Mill, South Carolina, conditions, pay, and hours had markedly improved from Ella May’s day. Improved, but still some of the hardest physical labor I ever did under some of the most taxing physical conditions.

On my first day, I was two months past my fourteenth birthday. I was summer labor, a spare hand, working a six until two shift at whatever hell my second hand decided. Doffing cloth, filling batteries, taking up quill and skinning them were my primary chores. I must have done okay, I was invited to continue, working weekends during the school year.

The early shift allowed enough daylight in the evening to pull four additional hours hoeing corn, picking beans or tossing square bales onto the bed of an old flatbed for two dollars a day. I was bone-weary at the end of the day and slept the sleep of the exhaustedly pure of heart, but in my immature brain, I was rich.

A dollar sixty-five an hour, time and a half for overtime over forty hours, plus the six dollars a week I got for tossing hay. $93.80 a week before taxes for seventy-two hours counting four overtime hours…all hard work. That was in 1964 and I wasn’t as rich as I thought. My parents took half my take-home pay for room and board and I was forced to save half of my half for the college days looming in the near future.

My week’s take came out to about fifteen dollars a week in my pocket…more than what Ella May made for seventy-two hours in 1929. Six days a week, twelve hours a day for $9.00 a week in conditions you can’t believe unless you lived it. $9.00 to house, feed and clothe herself and her five living children. She had lost two children in early childhood who developed rickets due to malnutrition. She was pregnant at the time of her death.

South Carolina has never been receptive to unions…the South has never been receptive to unions. As of 2017, only 2.6 percent of the Southern workforce was unionized. During Ella May Wiggins’s day, unions had only just begun to move south and were met with a solid, often violent, effort to keep them out.

On my first day at Springs, a cousin, Charlie Wilson, took me aside and yelled his whisper above the din of eleven hundred looms, “Never mention the word union if you want to keep your job.” I’m not sure I had heard of the word at the time but never mentioned it even though many days I doubted I really “wanted to keep my job.”

Despite the mind-numbing sound and physical labor, I was spoiled and didn’t know it until I went to work for another cotton mill during my college days. Springs Mills was a Cadillac of cotton mills. Well lit, it was reasonably modern and technologically advanced, cleaner than most, with a family atmosphere.

The two mills I worked at in Newberry, SC, during my college years were everything Springs wasn’t including an “every man for himself” atmosphere. Dimly lit, the old Draper looms were contrary and dangerous, the closed painted over windows a reminder of what was just on the other side…bright sunshine and clean air as opposed to the oppressive, lint filled atmosphere and heat inside.

As I lived through a week that saw a major drop in the stock market and a toilet paper panic, I am somberly amused at some of the similarities that exist today as in those thrilling days of yesteryear. Conservatives attempting to hold the line, liberals clamoring for change. Name-calling, finger-pointing and unfortunately threats to our democratic system if not our very person.

I hope most threats are coming from internet trolls with nothing to do as we “hunker down”, self-isolating ourselves from the coronavirus, worrying about where our next toilet paper score might occur. We can’t even agree if this disease is a health threat or simply the flu blown up by a liberal media controlled by communists and George Soros. I digress with tongue in cheek.

The reason for the Loray strike were workers protesting for better working conditions, a forty-hour workweek, a minimum $20 weekly wage, union recognition, and the abolition of the stretch-out system, a system that doubled worker’s labor but reduced their wages as textiles fell on hard times after The Great War and the drying up of government contracts.

The numbers and issues may be different, our responses have been eerily similar. It would be during the middle of the Great Depression before minimum wage, the forty-hour workweek and child labor, along with the Social Security safety net, would finally be addressed…all maligned at the time as at best socialism, at worse communism, both a threat to American capitalism and the owners it made rich.

In 1929, company men labeled any check to unlimited capitalism as Marxist, socialist or communist, and yes there were more than a few of them around. Ella May’s National Textile Workers Union certainly had communist ties, not that Ella May and her fellow workers knew what a communist was. She was simply seeking a better life for her children and herself.

I see the same labels raised when we debate increasing the minimum wage, health care, safety nets or educational opportunities. Labeling has become quite acute with both our political parties battling to pass a coronavirus relief bill.

Union enrollment is on the decline while finger-pointing increases. There is no middle ground. Signs of the time…or as my Evangelical friends shout, “Signs of the Apocalypse. The time is nigh.”

I wonder if we are nearing a tipping point when the national guard, new wave strikebreakers, and the police force will be employed to evict and expel people whose opinions simply differ. Couldn’t happen, could it? Yet in 1929 it did, and the violence would continue well into the Thirties.

Violence spurred by unchecked capitalism, fears of communism and being forced to work side by side with those of a different race. All supported by a sympathetic conservative media, and government “for and by” the “Captains of Industries.”

On April 1, 1929, eighteen hundred workers walked off the job at Loray in Gastonia, mostly women, some marching with babes in arms. Management evicted them from company housing, throwing their meager possessions into the street. One striker was killed, many beaten.

The North Carolina National Guard was called out on the third of April, violence erupted sporadically over the next several months. The police chief was killed, strikers and company men shot or beaten, and in September, a truck carrying twenty-two strikers was chased down and shot up. The pregnant organizer and singer of ballads, Ella May Wiggins, was killed, shot through her chest. Her children sent to an orphanage until their eighteenth birthdays.

A general wave of vigilantism washed across the countryside, company men arriving in the middle of the night, forcing strike participants out of the county in exile. These were their neighbors, people they knew by name, people they might have worked with just a few weeks before. People threatened with bodily harm if they returned.

The struggle continues today just not in US textiles. Textiles left the South for climates more receptive to low pay and long hours. There are a few specialty mills around but we simply can’t compete. Our standard of living requires we have a higher level of poverty than places like China, India, and Pakistan. Hopefully a higher level of empathy for our workers…but I am unsure.

***

I recommend The Last Ballad. Again, I warn you, it is a painful history brought to life by Wiley Cash. It is a history I was unfamiliar with even though I possess a history degree and lived within an hour of Gastonia and the Loray Mill site. We Southerners have a tendency to overlook or twist some of our more unsavory histories. This one seems to have been ignored.

The book may be purchased on Amazon or if you have a library card, downloaded to a Kindle or computer with a Kindle App for free. Yes, I’m cheap. https://www.amazon.com/Last-Ballad-Novel-Wiley-Cash/dp/0062313118

Don Miller is a retired educator and coach. He writes on various topics and his author’s page may be accessed at https://www.amazon.com/Don-Miller/e/B018IT38GM

Images

Featured Image: A member of the NC National Guard forcing two female strikers back. https://wilsoncountylocalhistorylibrary.wordpress.com/tag/ella-may-wiggins/

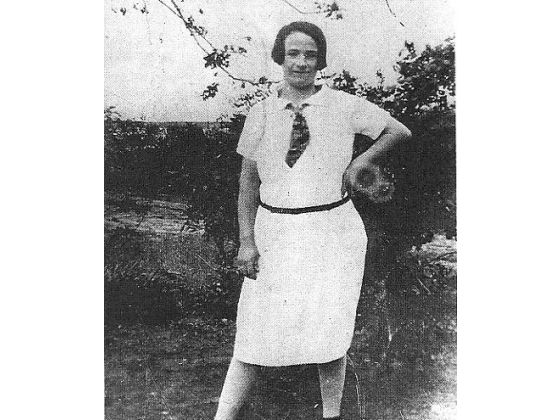

The first image is of Ella May (spelled Mae on her grave marker) Wiggins just before her death, https://www.charlotteobserver.com/entertainment/arts-culture/article175129556.html

The second image is of a young girl tending spinning frames in the early 1900s https://www.pinterest.com/pin/83457399315355531/

The third image is of Loray Mill strikers who walked out on April 1, 1929.

The fourth image is of the truck that carried Ella May Wiggins to her death. https://www.shelbystar.com/news/20190405/1929-loray-mill-strike-gastonia-violence-makes-waves